Lifelong Learning with Laura Cathcart Robbins

What addiction has taught the author of STASH about the power of reinvention and shaking ourselves awake to our lives

Last month, my friend (and author of the new book Can Anyone Tell Me? Essential Questions about Grief and Loss) Meghan Riordan Jarvis gathered a group of writers, therapists, and experts for Grieftastic, the first-ever conference and book fair centered on…yep, grief.

Though I expected a day of tears and sadness, what I experienced instead was deep admiration and connection with a group of individuals who are out in the world doing a tremendously hard and important thing: educating others about grief.

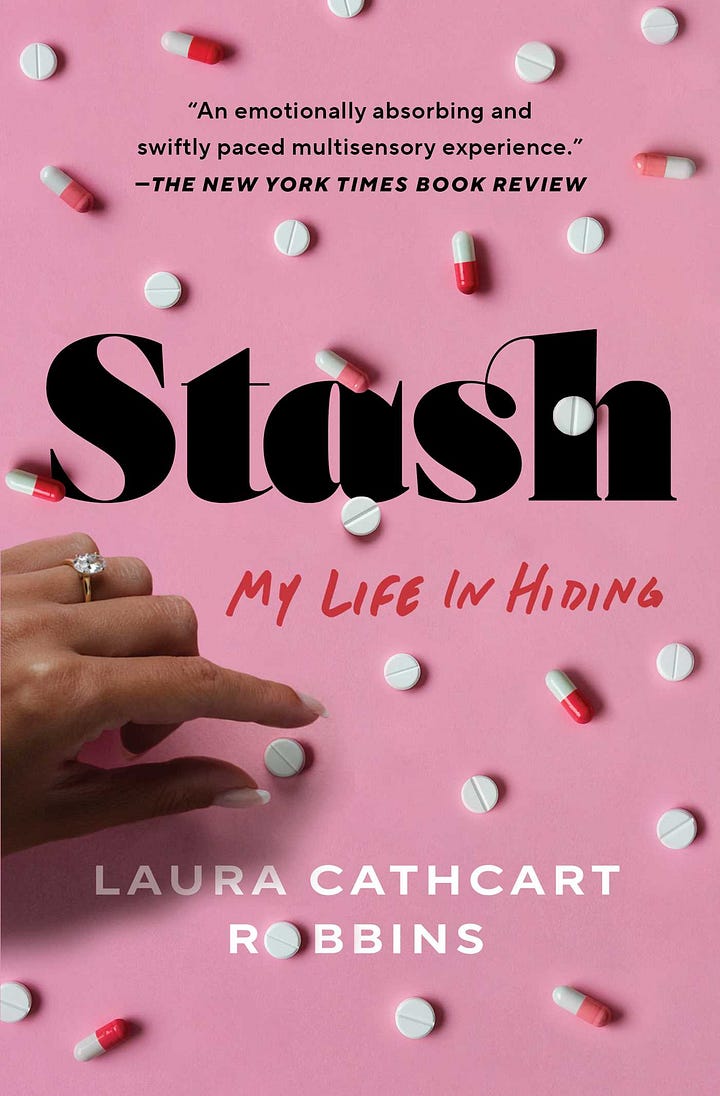

At the conference, I had the privilege of sitting on a panel with some dope-ass women who know a thing or two about grief and transformation. Among them was Laura Cathcart Robbins, author of Stash: My Life in Hiding, and the fantastic podcast The Only One in the Room, which evolved from a viral piece Laura penned back in 2018 about being the only Black woman at a writing weekend headlined by Elizabeth Gilbert and Cheryl Strayed (for the record, I was at this retreat too, and now regret the opportunity to have met Laura much earlier).

Laura and I share a mutual friend (kindred spirit Reema Zaman), and as someone who devoured Stash when it came out, I felt the way many readers do when they meet a beloved memoirist: like we were already friends.

That’s why I wasn’t surprised to discover Laura is as sharp, brilliant, and wise in real life as she is on the page. Her life has been full of surprising mile markers (I know zero other people who went from waitressing at the Marriott to running their own PR firm to marrying a Hollywood exec, going to rehab, and later becoming a nationally recognized author and speaker). Throughout it all, Laura has been her own best teacher in life, constantly reinventing herself and adapting to new circumstances. It’s no exaggeration to say she’s lived multiple lifetimes (even if she doesn’t look a day over 40).

I knew Laura would be the perfect voice for Lifelong Learning, so I summoned all my beefy audacity (a topic I wrote about earlier this week) to invite her to join me in conversation.

I’m so glad she said yes.

Will you start by talking about the story behind Stash? (I know it’s never easy to describe your own book.)

Stash covers a 10-month period in my life. On the surface, I had a glamorous Hollywood lifestyle as the wife of a feature director, with two young kids and a leadership role at their elite private school. But behind the scenes, I was battling a debilitating Ambien addiction.

People often ask, “How can you get addicted to a sleeping pill?” I used it as prescribed for a couple of years, but I built a tolerance and needed more. By my sixth year of use, it was completely out of control.

The book begins with me asking for a divorce, which frames the journey. I won’t spoil the ending, but there’s heartbreak, grief, and letting go of old ideas about what my life should look like. There’s even a love story woven in.

There’s a through-line in your story about getting honest with yourself. It’s bigger than just getting sober. Can you talk about how that theme shows up in other areas of your life?

I grew up living two lives: the one I presented to the world, which was carefree and glamorous, and my real life at home. My stepfather found everything about me—my authenticity, my genuine self—annoying, so I learned to edit myself.

I also grew up Black in predominantly white spaces, which required constant assimilation. It wasn’t just code-switching; it was survival.

In high school, I was seen as a star student, but I struggled academically, especially in STEM subjects. I fell behind, dropped out without telling anyone, and pretended I was still attending. I didn’t see it as hurting anyone; I just didn’t want to be investigated.

When I got sober, I realized that to keep my kids and stay connected, I needed to get honest. That was almost as painful as drug withdrawal.

How has the concept of hiding informed your parenting?

I’m very sensitive to my kids’ struggles. For example, when my younger son hid his bottle-cap city project in third grade because fine motor tasks were hard for him, I had to tell him it was okay to be different while also supporting him to complete the task.

Even after my ex-husband and I divorced, we co-parented closely. We didn’t want to modify our kids to fit their environment; we found environments that adapted to them.

When our older son’s college counselor suggested he might need to go to community college, we weren’t upset. He wanted to be a chef, so he went to culinary school and he’s now a chef at a restaurant in Montecito.

We were privileged to provide a safety net for our kids, and I recognize not all families have that. Some parents have to push harder because education is their child’s ticket out.

Publishing a memoir is like standing in Times Square naked. How did you step into the world as your full self?

I’ve always written—journals, stories. Sobriety taught me to tell my story, though at first, I curated it carefully to avoid judgment. Over time, I realized that being real warmed up the room.

Writing Stash wasn’t as scary as I thought because I was already practiced at sharing my story. My biggest fear was how people in the book would react, not how strangers would judge me.

Was the reception better than you anticipated?

Yes. My sons haven’t read it—they’re not memoir readers—but they’re proud of me. My ex-husband was generous and gave me permission to write about our shared experiences, even though I didn’t technically need it.

My friends were shocked. They knew about the divorce but had no idea about the addiction. Two didn’t even know I went to treatment.

You’ve said your kids were your reason for change. We don’t hear enough stories about children being the catalyst for transformation.

My connection with my kids was like nothing I’d ever experienced. I still love snuggling with them, even though they’re grown men with girlfriends. That connection was a powerful motivator.

My relationship with Ambien was also romantic in a way. I loved it, yearned for it, and missed it when it was gone. But now, I don’t romanticize it. I scorched the earth with it and never want to go back.

Were you journaling during your addiction?

Oh, absolutely. I kept detailed journals throughout my addiction, filling them with notes and even Polaroids. That documentation was incredibly helpful when writing Stash.

Your book acknowledges that memory is imperfect, especially during challenging times. Memoir readers should remember that while we may not recall exact details, we do remember how we felt.

I have what I call a revisionist memory. For example, I’ve always told this story about living in Denmark with my mom when I was four. I’ve said we lived there for six months, but I recently learned it was only two months. My memory created a whole world around that story, but it wasn’t accurate.

That’s why I fact-check when I write. If I say I was listening to a song, I’ll check if that song was even out at the time. If it wasn’t, I’ll choose another song from that era. The details might not matter as much as capturing the essence of the moment.

What have been the greatest gifts from the chapter of your life that’s captured in Stash?

The biggest gift is that I no longer want to escape my life. I genuinely embrace being present. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy a Netflix binge or cozying up by the fire, but I’m aware of how painful it was to escape the way I did for so many years.

Honestly, I should be dead. I was taking lethal amounts of Ambien and washing them down with alcohol daily. I didn’t realize how dangerous it was at the time—or maybe I didn’t want to know. I thought I was being careful, but I was reckless.

Now, I don’t romanticize my addiction. I remember how much I loved Ambien, but I also remember the excruciating withdrawal. That memory outweighs any temptation. I want to be present for my life, even when it’s hard.

It's interesting to me that the lessons from sobriety tend to be the lessons that all people need.

I think recovery work, whether it’s in the context of AA or another room, is really about self-examination with the help of someone else. It’s about confronting who and what you are, along with the desire to see what you could be. To me, defining that new path is recovery.

What are you working on learning now?

I’m working on letting go. When I want something—like selling my second book—I’ll do everything in my power to achieve it. But once I’ve done all I can, I have to release the outcome.

For example, my second book is autofiction based on my time as a publicist in the ’90s. I’m rebuilding my platform to include fiction while maintaining my identity as a memoirist and someone in recovery. I can do all the work, but whether the book sells isn’t up to me.

Rejection is part of the process. I’ve learned to see rejection as a call to action: What can I do differently? How can I support myself through it? It’s not personal; it’s about taste and preference. I’ve learned to leave no stone unturned and then let go of the results.

Read Laura’s recent Modern Love column here (and learn the surprising and beautiful story of how she met her partner, Scott) or listen to the episode below:

Connect with Laura at her website // Instagram // TikTok // Facebook